tl;dr: use ReLUs by default. Don’t pretrain if you have lots of labeled training data, but do in unsupervised settings. Use regularisation on weights / activations. L1 might promote sparsity, ReLUs already do and this seems good if the data itself is.

This seminal paper settled the introduction of ReLUs1 into the neural network community (they had already been used in other contexts, e.g. in RBMs.2

rectifying neurons (…) yield equal or better performance than hyperbolic tangent networks in spite of the hard non-linearity and non-differentiability at zero, creating sparse representations with true zeros, which seem remarkably suitable for naturally sparse data

Back in the late 2000s, layer-wise pretraining was introduced to prime neural networks, achieving significant improvements in performance.3 The authors used the now classical max(0,x) function together with

an L1 regularizer on the activation values to promote sparsity and prevent potential numerical problems with unbounded activation,

as well as pre-training using denoising autoencoders and found that:

surprisingly, rectifying activation allows deep networks to achieve their best performance without unsupervised pre-training.

It is however noted that unsupervised pre-training can help when much of the training data is unlabeled (in semi-supervised settings)

[Let’s skip the brain stuff, which is always pretty unconvincing anyway…]

A very interesting feature of ReLUs is that they induce sparse representations because they can be completely off. The authors give four reasons why this is good:

- “Information disentangling”: small perturbations of the input are less likely to shift many weights in the network if many of them are zeroes.

- “Efficient variable-size representation”: Varying the number of active neurons allows a model to control the effective dimensionality of the representation for a given input and the required precision.

- “Linear separability”: having many zeroes in a (high-dimensional) representation makes it more easily separable with linear boundaries.

- “Distributed but sparse”: albeit of lower expressivity than dense

representations, being still distributed makes them “exponentially

better than local ones”.

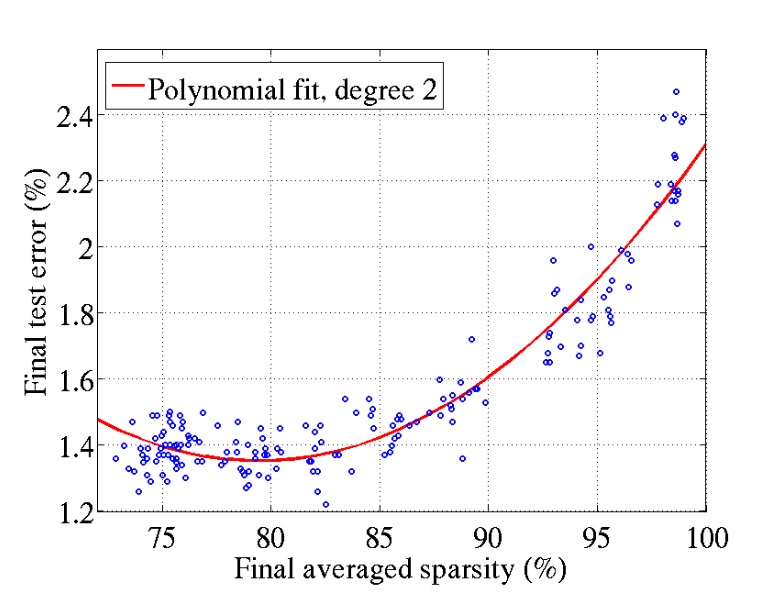

enforcing sparsity of the activation does not hurt final performance until around 85% of true zeros.

The ReLU acts like a switch. A unit either works linearly or not at all. This asymmetry might create some issues (see below) but it has the advantage that for any fixed input, the whole network is linear and thus can be seen as an “exponential number of linear models that share parameters”.

This is very reminiscent of the interpretation of Dropout as an extreme form of bagging.4 But perhaps more importantly, gradients flow backwards unhindered in active neurons, thus facilitating learning and alleviating the vanishing gradient problem. This is typically seen as the reason why ReLUs perform so well, brain stuff notwithstanding.

What are some possible disadvantages of ReLUs? Experimental results show that the non-differentiability (“hard saturation”) is not an issue, as long as enough hidden units are non-zero. However, with unbounded activations network weights might grow indefinitely if no regularisation is used and the authors used an L1 penalty term in the cost to promote further sparsity (think of the Lasso and how the L1 norm approximates the “counting zero entries” norm). Finally,

rectifier networks are sub ject to illconditioning of the parametrization. Biases and weights can be scaled in different (and consistent) ways while preserving the same overall network function.

This will be important later in their experiments.

Using ReLUs in autoencoders for unsupervised pre-training presents two main difficulties:

The hard thresholding at 0 impedes backpropagation of gradients during reconstruction: Indeed, whenever the network happens to reconstruct a zero in place of a non-zero target, the reconstruction unit can not backpropagate any gradient. In hidden layers this is probably not an issue “because gradients can still flow through the active (non-zero) [gates], possibly helping rather than hurting the assignment of credit”.

As already mentioned, regularisation is required to keep weights from growing unchecked.

Four different combinations of modified activations and cost functions are proposed:

The results of the better performing strategies A and B are detailed over four datasets: MNIST, CIFAR10, NISTP and NORB. They used stacked denoising auto-encoders with masking noise as the corruption process and posterior supervised fine-tuning with negative log-likelihood as cost function over a softmaxing of the outputs. Besides the already mentioned L1 penalty on the activations, they used standard minibatch SGD and no other regularisation. An important detail of their setup was:

To take into account the potential problem of rectifier units not being symmetric around 0, we use a variant of the activation function for which half of the units output values are multiplied by -1.

The Softplus is a smooth approximation to the ReLU

Interestingly, they tried a cost function interpolating between softplus and ReLU and by moving the parameter in its whole range and found that there is no performance gain in using the smoother activation over the ReLU. Therefore, rectifier units are preferable due to their being computationally cheaper and inherently sparse (an average 70~80% of the hidden units inactive in all tests!). Furthermore, pre-training achieved almost no improvement in fully supervised tasks, hinting again at how ReLUs enable more efficient searching of the energy landscape.

However,

In semi-supervised setups (with few labeled data), the pre-training is highly beneficial. But the more the labeled set grows, the closer the models with and without pre-training. Eventually, when all available data is labeled, the two models achieve identical performance.

Finally, tests on textual data for sentiment analysis and review ratings are performed. ReLUs seemed to perform very well and adapt to the inherent sparsity of the data, due to its representation using bag-of-words and binary vectors to encode presence/absence of terms. Pre-training was crucial here and architectures tanh activations were outperformed. The final ReLU networks displayed an average sparsity of around 50%, still much lower that the average of 99.4% zero features in the data, but a significant improvement.

- The name ReLU was not used in this paper so we are indulging in a bit of an anachronism by using it. ⇧

- Rectified linear units improve restricted boltzmann machines, (2010) ⇧

- Greedy layer-wise training of Deep Networks ⇧

- Improving neural networks by preventing co-adaptation of feature detectors ⇧