This paper introduced the now pervasive dropout regularisation technique. The basic idea is that

On each presentation of each training case, each hidden unit is randomly omitted from the network with a probability of 0.5 (…)

The intuition behind this is that silencing random networks at each iteration (about 50% of them), effectively training so many different networks, prevents the neurons from “co-adapting”, i.e. from relying too much on each other for their outputs.

But since we are training a new network on each training sample, we need to begin by moving fast in the landscape of the cost function. In order to achieve this, an additional technical step can be taken to enable high learning rates: the authors renormalized the weights for each neuron individually if a threshold for their (individual) L2 norm was surpassed:

Using a constraint rather than a penalty prevents weights from growing very large no matter how large the proposed weight-update is. This makes it possible to start with a very large learning rate which decays during learning

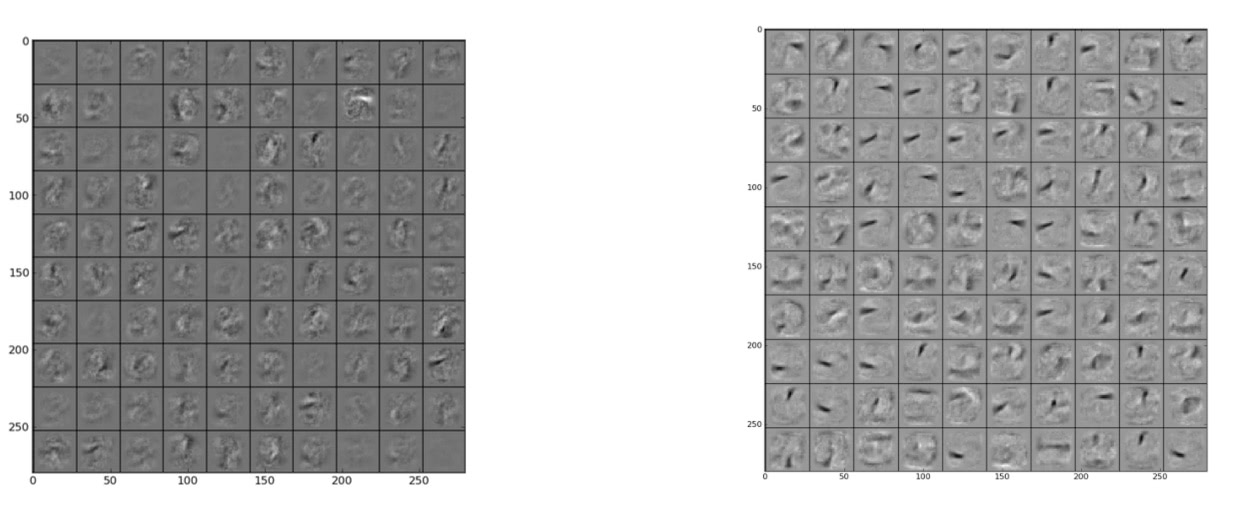

In Figure 5 of the paper:

Visualization of features learned by first layer hidden units for (a) backprop and (b) dropout on the MNIST dataset.

one can see that with dropout, features of the first layer are sharper and can be more easily interpreted as strokes than without it, where features appear blurred and more indistinct. This illustrates the key insight that we mentioned above:

[dropout] encourages each individual hidden unit to learn a useful feature without relying on specific other hidden units to correct its mistakes.

Because for each training example or mini-batch the network trained is a different one, dropout is a form of extreme bagging:

in which each model is trained on a single case and each parameter of the model is very strongly regularized by sharing it with the corresponding parameter in all the other models.

This turns out to be a very strong regulariser, which vastly improves the standard Lp penalty terms (probably also because of the additional induced sparsity in the final network, see Deep sparse rectifier neural networks for comments on how sparsity of representation improves performance for many tasks).

Having an ensemble of models reduces the variance of the estimator and improves generalization but at the cost that at test time we need to sample from a large number of dropout networks to approximate the posterior distribution.1 However, because models are given the same importance in the end, i.e. because the dropouts are independent, it is very cheap

to approximate the combined opinions of exponentially many dropout nets by using a single pass through the mean net.

The authors propose to approximate the expected output at test time by using the

“mean network” that contains all of the hidden units but with their outgoing weights halved to compensate for the fact that twice as many of them are active.

Notice that because of the non-linearities and multiple layers, one cannot simply compute the expected output of one neuron as a weighted sum over all possible combinations of (dropped) inputs.2 However, there exist some theoretical guarantees for toy networks that weighting at test time approximates the “expected network” (not in this paper).

In networks with a single hidden layer of N units and a “softmax” output layer for computing the probabilities of the class labels, using the mean network is exactly equivalent to taking the geometric mean of the probability distributions over labels predicted by all 2N possible networks. Assuming the dropout networks do not all make identical predictions, the prediction of the mean network is guaranteed to assign a higher log probability to the correct answer than the mean of the log probabilities assigned by the individual dropout networks (2). Similarly, for regression with linear output units, the squared error of the mean network is always better than the average of the squared errors of the dropout networks.

Finally, there is the possiblity of adapting dropout probabilities “by comparing the average performance on a validation set with the average performance when the unit is present.” thus achieving slightly better results.3

For datasets in which the required input-output mapping has a number of fairly different regimes, performance can probably be further improved by making the dropout probabilities be a learned function of the input, thus creating a statistically efficient “mixture of experts” (13) in which there are combinatorially many experts, but each parameter gets adapted on a large fraction of the training data.

Examples

MNIST: several fully connected networks, with momentum,4 exponentially decaying but large initial learning rates and 3-4 layers. p=0.5 dropout probability for the hidden layers plus 0.2 dropout for the input layer. Also: finetuning of Deep Belief Nets and Deep Boltzmann Machines.

TIMIT Acoustic-Phonetic Continuous Speech Corpus: extreme improvement in accuracy of pretrained models finetuned with dropout. No need to early-stop.

Reuters Corpus Volume I (RCV1-v2)

CIFAR10 and ImageNet: using convnets, pooling, ReLU activations,5 normalization of activations by regions (“local response normalization”), softmax loss, Gaussian initialization.6

- Recall that in Bayesian averaging one has an arbitrary posterior distribution over the models so that Monte Carlo methods have to be used to sample from it. ⇧

- See Understanding Dropout for more on this topic and some explicit computations. ⇧

- But Karphathy claims in CS231n, lecture 6, that this is not actually done in practice… ⇧

- On the importance of initialization and momentum in deep learning, (2013) . ⇧

- Improving neural networks by preventing co-adaptation of feature detectors . ⇧

- Now we know Gaussian init is bad! Cite… ⇧